How Google Maps APIs are fighting HIV in Kenya

In 2015, the Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) and mobile analytics solutions provider iVEDiX came together to create the HIV Situation Room, a mobile app designed to help fight the HIV epidemic in Kenya. The app uses Google Maps APIs to create a comprehensive picture of HIV prevention efforts, testing and treatment — and make this programmatic data accessible both to local staff in clinics and others on the front lines, as well as to policy makers.

We sat down with Taavi Erkkola, senior advisor on monitoring and evaluation for UNAIDS, and Brian Annechino, director of government and public sector solutions for iVEDiX, to hear more about the project and why they chose Google Maps APIs to help them in the fight against HIV.

How did the idea for the UNAIDS HIV Situation Room app come about?

Taavi Erkkola: As of 2015, UNAIDS estimates a total of 36.7 million people living with HIV globally. Of those, 2.1 million are newly infected, with approximately 5,700 new HIV infections a day. Sixty-six percent of all infected by HIV reside in sub-Saharan Africa, and approximately 400 people infected per day there are children under age 15. To effectively combat HIV, we need access to up-to-date information on everything from recent outbreaks and locations of clinics, to in-country educational efforts and inventory levels within healthcare facilities. UNAIDS has a Situation Room at our headquarters in Geneva that gives us access to this kind of worldwide HIV data. But we wanted to build a mobile app that provided global access to the Situation Room data, with more detail at a national, county and facility-level.

We tested out the app in Kenya because the country has a strong appetite for the use of technology to better its citizens’ health. Kenyan government agencies, including the National AIDS Council, encouraged organizations like Kenya Medical Supplies Authority (KEMSA) and the Ministry of Health to contribute their disease control expertise and data to the Situation Room solution. Kenya’s President Uhuru Kenyatta was an early advocate, and has demonstrated his government’s commitment to making data-driven decisions, especially in the fight against HIV and AIDS.

Why did UNAIDS and iVEDiX choose Google Maps, and how did you use Google Maps APIs to build the HIV Situation Room app?

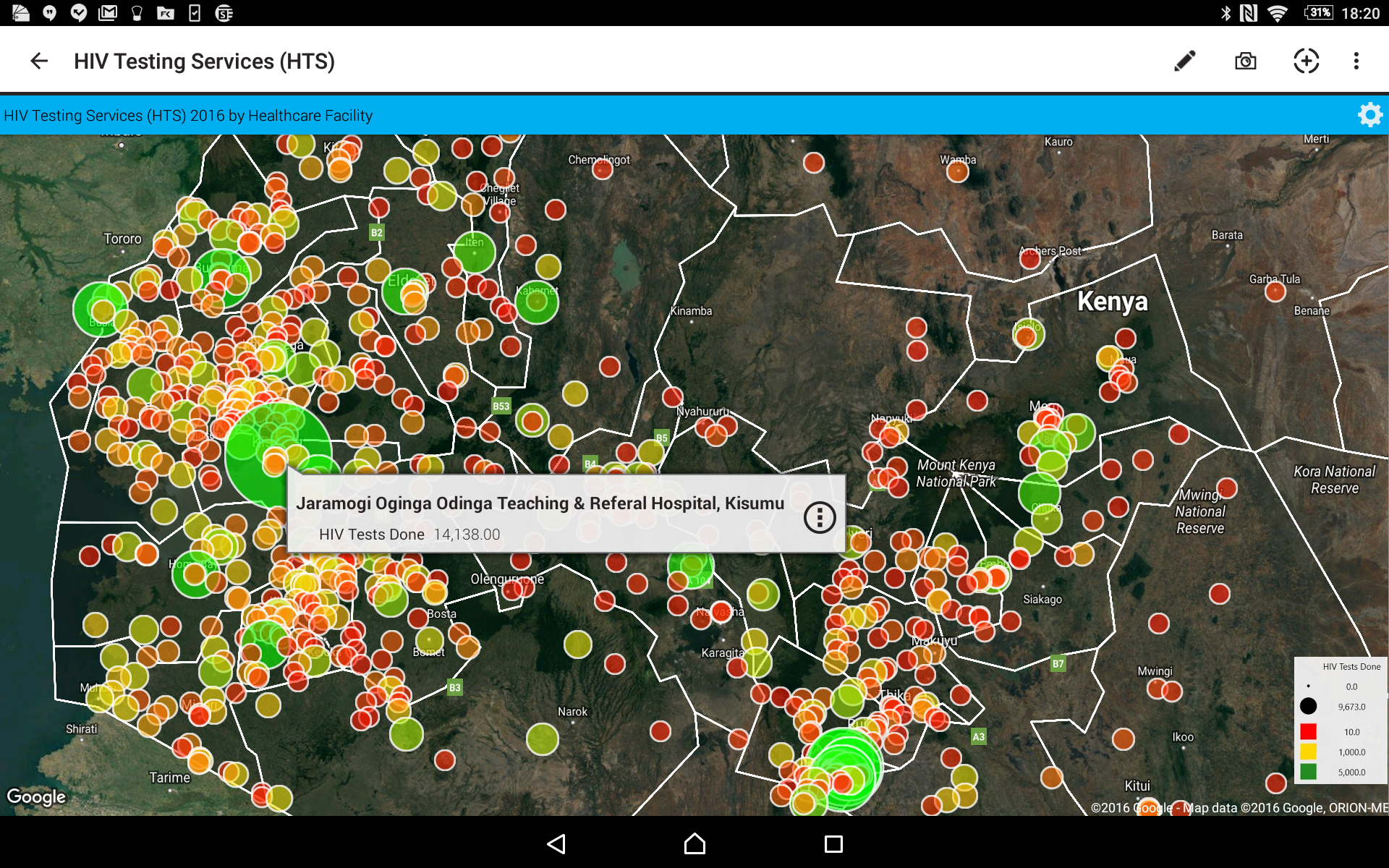

Brian Annechino: In Kenya, more than 80 percent of adults own a cell phone, and Android is by far the most popular operating system. Google Maps APIs are available across all platforms, including native APIs for Android, and Google Maps also offers the kind of fine-grained detail we needed — for example, the locations of more than 7,500 Kenyan healthcare facilities servicing the HIV and AIDS epidemic. Using data from multiple sources along with Google Maps, we can map things like a clinic’s risk of running out of antiretroviral medicine.

Onix, a Google Premier Partner, identified the right Google Maps components to build the app and helped us procure the licensing we needed. We used the Google Maps Android API to build the main interface. Since it was important to have the most accurate and up-to-date map data for Kenya to support the effort, we used the Street View feature of the Google Maps Android API to let people zoom into the street level and see clinics that offer HIV services in locations where Street View imagery is available.

TE: These mapping capabilities are critical because we need to give our county-level users as much insight as possible on service delivery at health facilities. Decision-makers in HIV response are at national and county-level. In this app, we’re able to combine multiple data sources to get a more comprehensive picture of HIV prevention efforts, testing and treatment across these levels.

What kind of data does the HIV Situation Room app display?

TE: The app taps into three data sources. The first is UNAIDS data set about country-by-country HIV estimates. The second is Kenya’s District Health Information System, which has detailed information from all 47 Kenyan counties — everything from the number of people treated at a specific hospital for HIV, to the number of HIV+ pregnant women attending clinics for visits, to the number of condoms distributed by each facility. The third data set will include community level data, which can also contain survey responses from clients about the quality of service they receive.

How does the HIV Situation Room use the data?

TE: By overlaying our inventory data and field notes on a map, we can see patterns and identify trends that help us respond quickly and plan efficiently. For example, if we see breakouts occurring in a particular area, we can monitor HIV test kits in that area or increase educational efforts for target communities.

Have you seen signs that your efforts are making a difference in Kenya?

TE: One of our biggest successes in Kenya is that the app is used by the highest-level decision-makers in the country — President Kenyatta uses the app — as well as people on the front lines fighting HIV, such as program managers. Using the app, policy makers have more information than ever before, and as a result, are able to devise more effective solutions by combining insights at the local and program coordination levels. We see it as an extremely powerful tool for fighting HIV — and we’re looking to bring this tool to other countries in Africa soon.